Posing at a cliffside high turn while biking the Yungas Road

At one point last week in my mountain biking tour of Yungas Road in Bolivia, a few other cyclists and I were, along with our lead guide, well ahead of the rest of our group. On a narrow stretch along a high precipice, our guide bid us to stop. He drew close to the cliff edge, and somberly pointed down below. Gingerly, we took a peek — and immediately gasped. A few hundred feet below was the mangled wreckage of a vehicle — a Toyota Land Cruiser, our guide explained, that just had its fatal plunge two weeks ago.

That type of tragedy is not uncommon on the infamous old Yungas Road, also known as the “Camino del Muerte” (Death Road), a route which gained a certain kind of notoriety in the 1990s when the Inter-American Development Bank dubbed it the “world’s most dangerous road”. Before a safer detour opened in 2006, the road claimed 200-300 lives annually, and was the scene of some horrific accidents. At the road’s narrowest point, recognizable to many from a memorable episode of BBC’s Top Gear, was the site of Bolivia’s worst-ever traffic incident. In 1983 a truck fell into the canyon, killing 101 passengers, all from the same village and returning home from a soccer match in the capital city of La Paz.

Nowadays, while there is much less automobile usage of the route, numerous crosses and monuments mark where unfortunate cyclists have met their end. Below, more about mine and Neil’s experience on the Yungas Road, and our time in La Paz.

Better Than Any Roller Coaster

Start of the downhill dirt road section of Yungas Road

A 2010 BBC News article perfectly summarizes the experience:

On its upper reaches, the clouds hug the cliff edge, obscuring the abyss. To the left, there is an unobstructed 600m drop off a cliff while on the right, a vertical rock-face. And the surface, which is unpaved, resembles a rough, dirt track more than a road.

The scenery, if you dare take your eyes off the road, is breathtaking, with the lush rainforest of the Yungas stretching out before you. But the stone and wooden crosses that line the route are a sombre reminder that not everyone cycles the full 40 miles (64km) safely to its conclusion.

Hurtling at 30mph (48km/h) down its dusty track … there is no expert guide controlling your propulsion. You are on your own.

The Yungas Road is a narrow, continuously winding, and incredibly steep road where at almost any moment you are responsible for preserving your life by not careening off a sheer cliff. In short, it was some 3 hours of non-stop adrenaline for myself, Neil, and the rest of our group of a dozen thrill-seekers on full-suspension downhill mountain bikes with hydraulic brakes.

On the morning of July 9, we started way high up at La Cumbre (altitude of 4,700m, or 15,400ft) in the freezing cold and bitter wind for a few practice segments on asphalt highway, before arriving at dirt road. The rest of the way is a bumpy, manic descent of 3,600m (11,800ft), with the temperature rising and us stripping off layers in stages, all the way down to the hot and steamy jungle voyage of Yolosa.

Early on we passed a stretch of road where just a week before giant boulders the size of vans had crashed down in a rockslide, leaving huge craters in the road that construction workers were trying to fix. As we continued along, aside from the sites of fatal car accidents, our guides (from the well-known Gravity Bolivia agency, who provided a great experience except that their promised “high-quality, professional” photos/videos from our tour were of horribly poor quality) pointed out spots where bikers had fallen or horror stories like that of a rider resting at roadside whose friend crashed into him and knocked him off the cliff.

One other interesting part of the road, which is one of the few linking the north of the country to La Paz, was having to pass on foot through a drug inspection checkpoint. This came into focus later on, when near the end of our ride, I saw a small coca field in the valley.

Horror stories aside, the ride actually wasn’t as scary as I thought it would be. After overcoming my initial instinct to rely on my brakes (slows bike but makes you very unstable), I quickly became supremely comfortable, zooming down the dirt and loose gravel at speeds up to 50km/hr (30mph). I felt an unbelievable adrenaline rush as I passed slower cyclists and at times cautious vans and buses, and wound up finishing all of the stages well ahead of almost all the other riders in our group. Most importantly, I never fell–proving this to be a safer adventure than my previous one on two wheels!

It was only on the return, while we drove back 3.5 hours to La Paz the same route we had biked downhill, when I noticed the thick fog that had set in. The road then seemed a lot more dangerous, and it was more difficult to believe we had just hurtled down this crazy route!

City of Peace

View from the Mirador Killi Killi

La Paz: where men in costumed zebra suits dance at busy intersections during rush hour to promote responsible pedestrian crossings; where heavily armed police are perpetually blocking off access to the plaza where the president works, perhaps as a result of lingering unrest; where men in ski-masks or balaclavas who approach you on the street want to shine your shoes, not kidnap you (supposedly they cover their faces because their work is considered shameful); where in a modern city, everywhere you see women dressed in traditional costume — the cholitas in their bowler hats and distinctive dresses; and where everything from taxis to dining out is so cheap you wonder if you have the right currency conversion rate.

Neil: “We don’t go on vacation, we do on-location photo shoots.”

My first impressions were that La Paz is chaotic, loud, and over-congested. But the more time I spent there, the more it grew on me, as I walked down the broad main avenue or through markets or up steep hills to turn, panting from the altitude, and catch great views. It is undeniably beautiful. Situated at 3,660m (12,000 ft), La Paz is built on a huge slope, where at the top and spreading over the plains is the city-within-a-city of El Alto, the center of Aymará culture and a rapidly growing hub of poor immigrant workers from throughout Bolivia. The rest of the city spills down into the valley and along the sides of the cliffs below for kilometers. On a handful of occasions I got to take in the breathtaking view of the valley at night from El Alto, when millions of the city’s lights stand out against the dramatic backdrop like so many fireflies or stars or jewels.

On our first night in La Paz, a Saturday, Neil and I committed the faux pas of going out too early, and we found it hard to discover any semblance of nightlife. (The other reason apart from the time was that the Bolivia Lonely Planet guide is woefully outdated, on everything from La Paz bars and restaurants to Oruro train schedules.) After dinner, we were grabbing drinks at Mongo’s while watching the UFC title match, when I befriended a cute local girl, Mirtha, who invited us to join her, her sister Tefi, and cousins. After enjoying a lively conversation at the bar over some local Huari beers, we headed out to a discoteca. It’s the kind of place we wouldn’t have found on our own: completely nondescript on the outside, but inside packed full of people dancing to music which ranged from Chili Peppers to cumbia. Unexpectedly, we stayed out til nearly 4am and got to see a great slice of local life thanks to some really cool Paceñas.

The next weekend, on Sun. night after Neil had started his return home, was a huge celebration to commemorate the Virgen del Carmen (La Paz’s patron saint) as well as the anniversary of an important historical event in the independence movement. The Plaza San Francisco, right near where I staying, was thronged with revelers drinking, batting balloons, and waving flags; and the main avenue at Avenida Mariscal Santa Cruz was closed off to cars and occupied by street vendors. I ate until I was bursting — sausage escabeche, steak and potatoes sandwiches, tripita (cow intestines) — and drank sucumbe, prepared by ladies in the street by boiling milk, water, and cinnamon, and whipping it until it reaches a foamy consistency. They fill a large glass with that, still piping-hot, and add a shot of singani (a Bolivian spirit similar to pisco). It does wonders to warm you up on a cold night.

16th of July celebrations in La Paz

At midnight, a huge fireworks display erupted, and the crowd broke out into chants of “Viva La Paz!” A concert on the huge stage set up for the occasion raged though the morning’s wee hours. The party didn’t need to stop–Monday was a national holiday, because as a taxi driver explained to me, “Es un dia para recuperar!” (it’s a day to recover!)

“In This Corner, in the Flouncy Skirt and Bowler Hat…”

Lucha libre in El Alto

Retelling our La Paz adventure wouldn’t be complete without mentioning that Neil and I attended the uniquely La Paz spectacle of lucha libre — a form of staged wrestling which draws from Mexico its masks and costumes and from the U.S.’s WWE its faux-violent antics. What makes it different than those is what gives Paceños and tourists so much glee: that the star attractions of the show are dressed as cholitas, complete with flouncy skirts and bowler hats.

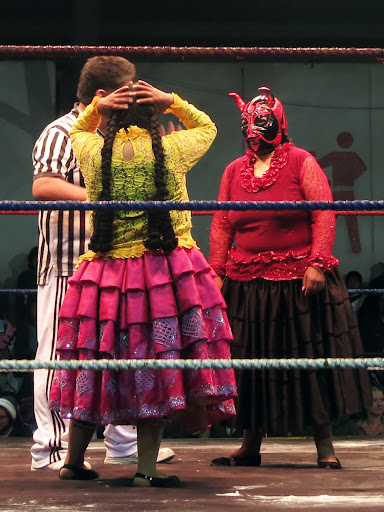

Cholita versus… some kind of devil woman? Oh, and the dirty ref, too

The action takes place in an auditorium in El Alto, and the scripts follow along the traditional lines of heroes and heels, betrayals, crooked referees, dirty tricks, audience involvement, and use of ridiculous props. At times the fights spilled out of the ring and even into the stands. Owing to the weekly event’s huge popularity in recent years, which has drawn many tourists, foreigners now pay a higher ticket fee (still only ~$7) and sit in folding chairs ringside, while locals sit in the bleachers. They often throw popcorn or drinks (or worse) at the villains they detest, and perhaps my biggest takeaway was learning a number of new Spanish expletives from the crowd’s chants!

Holy balls.

lol neil looks like abishek bacchan in that picture. in other news i’m glad you guys are alive!

I’d be even more terrified going up the Death Road in a fat, poorly maintained car than on nimble bikes, for sure 🙂

Neil, you are a sexy beast.

Do you think that the appeal of the bike ride is built upon the death and despair of those who have lost their lives and their loved ones? If so, can I interest you in a trip to Syria, North Korea, or Somalia?

Also, where is Mirtha?